Have you ever wondered how cage diving with great white sharks began? In Part 1 of our series, we look at the history of cage diving with great white sharks.

Last October it happened again: A video showed how a white shark broke through the bars of a shark cage in front of the Mexican island of Guadalupe. Not only was it horrible for the diver, but also for the shark. The animal had rammed the metal construction and became trapped.

Helplessly, the crew watched as the shark grew very agitated and distressed in the cage. They opened the lid of the cage in the hope it would get out. It took about 50 seconds until it became clear the diver was not injured.

The most battered was not the cage or the divers, but the shark, who had been panicking and trying to get out of the cage. It was hurt and swam away bleeding.

If you do internet research, you will find around a half dozen similar cases. Headlines such as “Shark Breaks through Cage Diving Rods” or “Divers in Danger of Life: White Shark Penetrates into Cage,“ rule the gazette and tabloid papers.

For years there has been a great controversy between animal protectionists and divers on the subject of cage diving. Some consider it to be irresponsible and demand an immediate stop of these excursions because the hunting instincts of white sharks are triggered when fed bait.

Sharks could become aggressive and lose their timidity against people. Many suspect a connection with the increasing attacks on swimmers and surfers off the coast of South Africa. In 2009 and 2010 alone, 14 incidents were recorded, and six people died.

However, advocates of cage diving claim that sharks are not fed, but only attracted and lured to the boat with chum. They believe, through this kind of encounter, people can recognize the white shark‘s value as a protected creature.

Time to take a close look at the history of cage diving.

It’s a strange thing with white sharks. While many scuba divers cannot get enough white sharks in front of their masks, most other people are happy they‘ve never seen one. The (wrong) picture of the beast lies too deep in our minds, about the killer with the jagged teeth, something peculiarly sinister.

It’s an eerie feeling to suddenly realize you are part of the food chain when you enter the ocean. You could be human prey and end up in a monster’s stomach. “What is a monster? To a mouse, a cat is a monster. We are just used to being the cat.”

This classic line from the movie “Jurassic World” shows the myth of antiquity when thinking about big predators. Some divers are concerned less about their lives when it comes to white sharks, but rather about how they can see the elegant predators. The solution—cage diving!

Twenty years ago, cage diving was reserved for daredevils and experienced divers. Nowadays, thanks to increased regulations and safety measures, housewives and even children can indulge this adrenaline kick. You do not need scuba diving training. Eye to eye with a white shark—for many it’s an item on a bucket list. That is why cage diving has now become a multi-million-dollar business.

There are only five places in the world where you can pursue this thrill. The most famous locations are South Africa (False Bay and Gansbay), South Australia (Neptune Islands near Port Lincoln) and Mexico (Guadalupe Island). In California, you have the Farallon Islands and, relatively new, the opportunity in New Zealand at Stewart Island in the very south. In these places, there are large seal colonies, the main prey of the white sharks.

Australia. How it all began.

No, once and for all, it did not start with Richard Dreyfuss as Matt Hooper and his jump into the cage in “Jaws.” Cage diving started in the late 60s, around Dangerous Reef and other places in the South Australian Spencer Gulf.

Experienced divers like Ron and Valerie Taylor, and Rodney Fox made the first attempts at cage diving. They benefited from South Australian fishermen such as Alf Dean, who had developed techniques to lure white sharks to their boats.

One of the most famous and widely-discussed shark incidents of all time is the attack on spearfisherman Rodney Fox which took place December 8, 1963, at Aldinga Beach, about 50 km south of Adelaide. This incident became so popular because Fox was the first person to survive a white shark attack and talk about it later.

The doctors used 462 stitches to sew him together and save his life.

Fox then came up with an idea. “My wife and I were at the zoo and we watched lions and tigers behind bars. The thought came to me. Perhaps one can also observe sharks from a cage. Around 1965 I organized an expedition with two other shark attack victims to observe white sharks.

“The animals were more interested in the bait than us. When I was in the water with those apex predators, I became aware that I no longer wanted to be an insurance agent. So I quit my job, started to collect abalone mussels and offer white shark trips,” he told TAUCHEN, a German magazine for divers.

Rodney made his plans and built the first two-man cage. He organized a new boat and found sponsors for the shark expedition. With guests, shark attack victims Brian Rodger and Henri Bource, Rodney called Ron Taylor to film the expedition in partnership with him. This was the first time great white sharks were filmed under water.

It was a turning point in the life of Rodney Fox. He discovered white sharks were not crazy about human flesh, but were fascinating and cautious creatures. Rodney, Ron and Valerie’s film, “Blue Water, White Death,” was a great success and was shown in 1971 in many countries around the world. During the shooting, large gorilla cages made of steel were used. This was safe, but also very time-consuming and cost several thousand dollars.

“Then I received this incredible call from Hollywood to see if I could help the film crew with real shark footage for “Jaws.” At this time, we had no idea that this movie would give the shark such a bad image. The film crew visited me in Port Lincoln where I lived. In addition, one of the screenplay authors came, Carl Gottlieb. They gave me their storybook and showed me what they needed. We filmed the white sharks in the next days from the right, from the left, from the top from below,” Fox said.

In 1976, shortly after “Jaws” was released, Rodney received a request from an American dive company who wanted to bring their customers on a shark expedition. Rodney was happy, and it was the world’s first cage diving tour, the first of many, as it turned out.

Immediately after that, the Taylors developed light-floating cages, which were more suitable for film purposes than the heavier ones used in commercial cage dive trips. The Taylors had found that heavy cages were unnecessary because sharks usually swam around the cages and did not even try to penetrate the cage. The result was light wire mesh cages with galvanized steel frames, side doors and deck flaps.

Personal experiences

Apex Predator. The Ultimate Killing Machine. The Perfect Hunter. When talking about white sharks, superlatives are fast at hand.

In every child’s card game it would be the trump card: the world’s biggest predator fish, the white shark. They are usually between four and five meters (16 ft) long and can reach a maximum of six meters (20 ft) and weigh more than two tons. I also wanted to see this animal live.

In 2001, I applied to the White Shark Research Institute in Gansbaai, South Africa as a student field assistant and was accepted. For three weeks, I could work with the world-famous shark expert Craig Ferreira.

Craig was one of the driving forces in a lobby that led to the protection of the white sharks in South Africa in 1991. It was hard to believe that his father Theo was a notorious hunter who later became an environmentalist.

Even today, the story about Theo Ferreira and his hunt for a notorious shark, which they only called Submarine, is still being told. This white shark was said to be as big as a submarine, supposedly seven meters (23 ft) in length and five tons in weight. Theo harpooned him three times, but he would escape again and again. Craig later transformed the adventurous hunt into a fictional story in his novel The Shark.

Of course, Craig also told me all about the biology, reproduction, and behaviors of the sharks themselves. The institute owned two boats, the Elasmo I , 12 meters (39 ft) in length, and the Elasmo II, 9 meters (30 ft) in length. Each boat had a cage.

To my great surprise, these were not heavy steel cages as I knew from the documentary Blue Water, White Death, but simple two-man cages made of wire mesh fence, reinforced only by steel struts. Also, the brochure with the Cage Emergency Procedures was not very encouraging to me if something went wrong. I was a little nervous when I read: Broken Air Line, Drifting Cage, Shark Entangled and Air Line Cut. I was ready to leave. That was only in case of emergency, Craig said with a broad grin on his face.

I had once believed where sharks are found, you only had to hold your bleeding finger in the water and they will promptly tear off your arm. I was now taught something better.

Our boat was anchored in front of Seal Island, 5 kilometers (3 mi) from shore. We dumped liters of chum (mashed up sardines) into the water. The minutes went by but nothing happened, nothing at all.

No sharks far and wide. It almost seemed to me that the seals were laughing at me with their staccato-like howling. “If a white shark was swimming here, we wouldn’t be in the water, fool,” they seemed to tell me.

The waves were unrelenting, and I tried to keep my balance on the boat. Although the nausea was increasing, I was pumped with adrenaline and my eyes continuously scanned the water surface for the infamous dorsal fin. Craig fastened two huge tuna-heads on a rope and threw them into the water.

“The bait leads the sharks to the boat and makes sure they stay here for a while. When a shark wants to catch the tuna bait, I pull it away and lure it closer to the boat so we can study it, as if you were attracting a donkey with a carrot,” Craig said.

“It’s about keeping the sharks by the boat, not feeding them with the bait, because they should not link boats and humans with prey,” the expert added.

After an hour or so, they came: first one, then two, then three and four. White sharks circled our boat. I could hardly believe my luck! Gracefully, their dorsal fins cut through the water surface, their torpedo-shaped bodies were simply enormous. These sharks were between three and four meters (10 and 13 ft) long, just a good average for a white shark.

But it is not purely length which takes one’s breath away; above all, it’s the girth. If you have never seen a shark in reality, let me tell you that sharks are not thin, slender fish, such as barracuda. Their bodies are massive and conical at the same time. Their chest fins act like the huge wings of a jet fighter!

The water was greenish and murky. Because of the bad visibility it was difficult for me to keep the individual animals apart. But after another hour, Craig told me that ten different sharks were swimming around our boat—ten!

The most fascinating thing was they were not at all aggressive. Rather curiously and carefully they approached the bait, snapped here and there for a tuna and dived leisurely. I understood quite quickly, these sharks were not brainless killer machines from the cinema, but highly developed and perfectly adapted predators.

This concludes How Cage Diving with Great White Sharks Began, Part 1.

Be sure to check back for How Cage Diving with Great White Sharks Began, Part 2, next week.

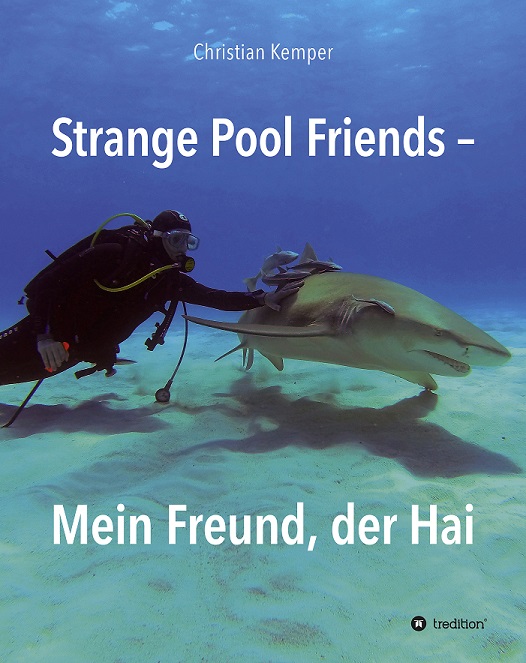

Christian Kemper is a TV journalist from Germany. He has been diving with and studying sharks for more than 20 years. He has written two books about shark attacks and one book about crocodiles. He is a freelance writer for 3 of the biggest diving magazines in Germany.

You can find his German Language book Strange Pool Friends on Amazon and at tredition.

He has also written a three part article about his scuba diving with tiger sharks at Tiger beach for Tracking Sharks.

This is the famous Guadalupe Island caged shark a few weeks later….

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VVLTI2xz-80